An Introduction to... Louis Jenkins

7/2/2011

Originally published on everythingbutamisprint.tumblr.com in February 2011. "Always be a poet, even in prose" —Charles Baudelaire There is much debate over prose poetry's right to exist as a literary genre. For many, the pairing of the two words to describe a piece of writing is oxymoronic; it seems that most critics cannot abide prose poetry's desire to place itself somewhere between the two forms of writing. Some argue that, due to its heightened attention to language and fondness for techniques common to poetry (such as metaphor, fragmentation, compression, repetition and rhyme) the form belongs to poetry alone, whilst others point in the opposite direction, towards an aversion to line breaks and a reliance on prose's association with narrative – perhaps evidence enough that it should be considered only under the prose genre's already vast umbrella. Peter Johnson, editor of The Prose Poem: An International Journal, suggests that "just as black humor [sic] straddles the fine line between comedy and tragedy, so the prose poem plants one foot in prose, the other in poetry, both heels resting precariously on banana peels." Prose poetry is described as such because of its fusion of prosaic and poetic elements; it is a literary hybrid that fervently refuses to be pigeonholed. Perhaps the most helpful definition comes from the Serbian-American poet Charles Simic, who likens the form to "peasant dishes, like paella or gumbo, which bring together a great variety of ingredients and flavors [sic], and which in the end, thanks to the art of the cook, somehow blend." Although the form is often traced back to French writers rebelling against the strict Alexandrine in the 19th century, examples of prose passages in poetic texts can actually be found in earlier works, such as Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads and The Authorised King James Bible. However, it was the ink of Baudelaire and Bertrand that presented the prose poem as a literary form in its own right, marking a significant departure from the strict separation between the two genres at the time. Spreading across countries and continents, the form found its way into the innovative literary circles of Rilke and Kafka, Borges and Neruda, Anderson and Stein (Anderson actually considered his work to be what we would today call 'flash fiction', rather than prose poetry – the lines between the two are often indiscernibly blurred).

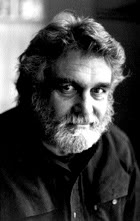

Although Charles Simic is certainly America's most well-known living poet to have dabbled in the art of this opinion-dividing form, Robert Bly suggests that "most people writing prose poems now agree that Louis Jenkins is the contemporary master." However, apart from the 15 minutes of fame brought by Mark Rylance's Tony Award acceptance speech (Rylance recited Jenkins' 'The Back Country' when receiving Leading Actor in 2008), the prose poet from Enid, Oklahoma has enjoyed very little time in the literary-limelight (although, you can't help but sense that suits him). When asked in an interview if he demanded anything from his audience, Jenkins replied: "Just attention for a few minutes. I don't have any illusions that my books are going to sell thousands and thousands of copies. It's a small audience." Flicking through his latest collection, North of the Cities, it's quickly apparent that Jenkins' poems are, at the very least, worth spending a few minutes on – almost always managing, as Annie-Marie Fyfe notes, to "distil a fine, dry wisdom from his apparent delight in the simple turn of the seasons, the muted exuberance of middle age, the inevitability of death –" A New Poem I am driving again, the back roads of northern Minnesota, on my way from A to B, through the spruce and tamarack. To amuse myself I compose a poem. It is the same poem I wrote yesterday, the same poem I wrote last week, the same poem I always write, but it helps to pass the time. It's September and everything has gone to seed, the maple leaves are beginning to turn and the warblers are on their way south. The tansy and goldenrod in the ditches are covered with dust. Already my hair has turned grey. The dark comes much earlier now. Soon winter will come. I sigh and wonder, where has the time gone? (North of the Cities, Will o' the Wisp Books, 2007) The meta-fiction poems collected in North of the Cities perfectly typify the contemporary prose poem: a snapshot of everyday life laced with sardonic humour that strives for sonorous effect. Perhaps a criticism of Jenkins' poetry might be that, in its desire to be easily accessible, it sometimes becomes a little too conversational, a little too (for want of a better word) simple. However, it is out of this 'simplicity' that the sonorous effect is often found. Squirrel The squirrel makes a split-second decision and acts on it immediately — headlong across the street as fast as he can go. Sure, it's fraught with danger, sure there's a car coming, sure it's reckless and totally unnecessary, but the squirrel is committed. He will stay the course. (North of the Cities, Will o' the Wisp Books, 2007) Simplicity in poetry is too often viewed in a negative light; "I think that one should be clear," says Jenkins, "so that the reader can at least understand whatever scene or object or whatever it is you're trying to describe...I don't think there's any point in deliberate obscurity." It is this clarity, as seen in 'Squirrel' and many others included in North of the Cities, that allows the poetry to arrive at what Robert Frost called "the momentary stay against confusion", something which Jenkins admits he strives to achieve: "[The poem is] a momentary way of ordering your experience into a group of words. Frost says "momentary" and that's the important word there; it's momentary, because you have to do it again. You don't actually make order in the universe; you only make a momentary stay against confusion." Earl In Sitka, because they are fond of them, people have named the seals. Every seal is named Earl because they are killed one after another by the orca, the killer whale; seal bodies tossed left and right into the air. "At least he didn't get Earl," someone says. And sure enough, after a time, that same friendly, bewhiskered face bobs to the surface. It's Earl again. Well, how else are you to live except by denial, by some palatable fiction, some little song to sing while the inevitable, the black and white blindsiding fact, comes hurtling toward you out of the deep? (North of the Cities, Will o' the Wisp Books, 2007) Louis Jenkins is, perhaps above all, a fantastic storyteller – a poet who, as one critic asserts, writes "short paragraphs that turn everyday life into sparkling bits of homespun philosophy." Jenkins says that although his work is not the continuation of any specific oral tradition experienced whilst growing up, there were always stories to be told or heard within his family; how uncle Ralph broke his leg in a motorcycle accident, how aunt Esther went crazy. "All poetry," he says, "comes down to storytelling. This is what happened. This is what it's like to be a live human being. You tell that story the best way you can." Uncle Axel In the box of old photos there's one of a young man with a moustache wearing a long coat, circa 1890. The photo is labeled "Uncle Karl" on the back. That would be your mother's granduncle, who came from Sweden, a missionary, and was killed by Indians in North Dakota, your great-granduncle. The young man in the photo is looking away from the camera, slightly to the left. He has a look of determination, a man of destiny, preparing to bring the faith to the heathen Sioux. But it isn't Karl. The photo was mislabeled, fifty years ago. It's actually a photo of Uncle Axel, from Norway, your father's uncle, who was a farmer. No one knows that now. No one remembers Axel, or Karl. If you look closely at the photo it almost appears that the young man is speaking, perhaps muttering "I'm Axel damn it. Quit calling me Karl!" (North of the Cities, Will o' the Wisp Books, 2007) 'Uncle Axel' taps in to that human desire to be remembered beyond our years, and comments upon how fragile the memory of our existence becomes as the decades race by. The identity of the dead can be drastically altered by such a small mistake made by the living – a mislabelled photograph has seemingly erased Uncle Axel from history. From beyond the poem's comic surface comes the most tragic of echoes. And so, taking into consideration his Rylance-inspired 15 minutes of fame, how would Louis Jenkins like to be remembered? "Someone once said that to be a famous poet is like being a peanut at a banquet." Perhaps, then, as a storyteller, or, as Robert Bly suggests, the best prose poet of his generation? "I want to be a cloud," Jenkins writes in 'Ambition', "…I'd like to be one of those big fat cumulus clouds that pass silently overhead on a beautiful day. A day so fine, in fact, that you might not even notice me, as I sailed over your town on my way somewhere else, but you'd feel good about it." For more information about Louis Jenkins, and some further examples of his poetry, visit http://www.louisjenkins.com or his unofficial Facebook page http://www.facebook.com/pages/Louis-Jenkins/110505162316832 North of the Cities’ is available to buy from http://www.willothewispbooks.com Everything But A Mis-Print is a poetry-centric blog which hopes to introduce the world to the little-known poets worth knowing about. From the serial small-press chapbookers to the well-respected wordsmiths largely unread outside their own countries, the EBAM blog strives to place a spotlight on the very best poetry that swims outside the mainstream. You can visit it here: everythingbutamisprint.tumblr.com

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed